Exploring Textile Artistry in Iceland: My First Month at the Os Textile Residency Centre, May 2023

- Lucy MacDonald

- Jun 4, 2023

- 9 min read

Updated: Mar 23, 2025

Blönduós, a small town in the north of Iceland, is home to the Icelandic Textile Centre, a renowned institution that celebrates and promotes the art of textiles.

Most of the industry and livelihood in Blönduós has evolved around service for agriculture and tourism. In recent years, the town has become more well known for its connection with textiles. A wool washery, Iceland's only textile museum Heimilisiðnaðarsafnið and the Textile Centre, are all located in Blönduós.

The Textile Centre is a hub for the community, acting as a base for a variety of events. They host local school visits, resident artists from around the world along with visits from members of the community to bring textiles to a wider audience.

My residency stay was for two months; May and June and I had plenty of work to keep busy with!

1. Immersion in Icelandic Landscapes and Seascapes:

During my first week in Iceland I rented a car so that I could explore the local area and take photographs which would direct my weaving later during the residency. I travelled to a variety of different locations and landscapes;

Hofos, Hvitserkur, Skagastrond, Saudarkrokur on the coast

Myvatn, Varmahlio, Holar, Hverir, Dimmuborgavegur, Dettifoss and Selfoss inland.

Akureyri and Husavik on fjords.

The landscapes and seascapes were incredibly varied with lava fields, mountain ranges, geothermal areas and dramatic coastlines. It gave me a huge collection of images to work from and to base my yarn colour palette on.

I find using my own photography as a starting point to be useful for a number of reasons;

Exploration and Observation: Photography allows me to explore and observe the world around me with a focus on both the large landscapes but also the micro details within a set frame. By immersing myself in the environment I noticed details, patterns, and unique elements which might have gone unnoticed otherwise. The process helps to train my eye to identify interesting visual elements which I can then translate into design concepts.

Inspiration and Mood: Photographs have the power to evoke emotions and convey a specific mood or atmosphere. The colours, lighting, and composition of a photograph can inspire a particular feeling or aesthetic. By basing my sketchbook designs on my photographs, I can extract the essence of the captured moments and use them as a starting point to define the mood and direction of my woven designs.

Colour Palette: Photography provides a rich source of inspiration for colour palettes. I use the colours present in my photographs to identify harmonious combinations and explore the potential for translating those colours into my design work. This way of working ensures that my designs are rooted in the natural and harmonious colour relationships found in the landscapes which they depict.

Textures and Patterns: The photographs captured intricate textures and patterns found in nature. These visual elements served as a foundation for creating the threading pattern on the loom.

Composition and Layout: Photography offered an insight into the composition of a design. By studying the composition of my photographs I was able to experiment with different placements and focal points, within my sketchbook. Hopefully this will help my designs have a strong visual impact and a sense of balance.

2. From Fleece to Yarn: Carding, Blending, and Hand Spinning Icelandic Fleece:

I chose Icelandic fleece in five shades to create my weft yarns with; light grey, dark grey, black, white and brown. My first step was to put the washed fleece through a Drum Carder:

The Drum Carder consists of two rotating drums covered in carding cloth, one drum is called the infeed drum, and the other is the main drum.

Feeding the Fleece: Sections of the prepared fleece was fed onto the infeed drum. The teeth on the drum carder helped align the fibers and removed tangles as the fleece passed through.

Carding Process: As the fleece passed between the drums, it underwent carding, which aligned the fibres and blended them together. This process was repeated with additional fleece sections until I had carded all 50g of fleece and was ready to start the next one.

Colour Blending:

Preparing Fibre Colours: I weighed out different quantities of fleece in 50g bundles so that I could spin a range of natural coloured shades.

Blending Colours: The fleece was passed through the drum carder multiple times to create a blended fibre batt with varied colors ready to spin.

Hand Spinning on the E-Spinner:

Fibre Preparation: I divided the blended and carded fibre into smaller, more manageable portions making it easier to draft and easier to spin.

Spinning Process: I attached the fibre to the leader string on the e-spinner's bobbin then spun by drafting and drawing it out as the e-spinner twisted it into yarn.

Finishing: Once all 50g of yarn was spun it was removed from the bobbin. I set the twist by gently soaking the yarn in lukewarm water, allowing it to relax, and then it was hung out to air dry (more like air blown in the Icelandic wind!)

I found that using an e-spinner simplified the hand spinning process by automating some aspects, such as controlling the twist and tension and allowed me to produce a lot more yarn than I would have been able to with a traditional treadle spinning wheel.

3. Natural Dyeing: Foraging and Experimenting:

Whilst I had access to the car, I also took the chance to go foraging for local dye plants and seaweeds to use for natural dyeing. During my foraging adventures, I ventured into meadows, a rare Icelandic pine forest, and along the coastlines, carefully identifying and gathering plant materials. The northern Icelandic region offered a diverse variety of plant species, including willow, birch, heather, lupin, angelica, and various lichens. These plants provide an extensive palette of colours, from earthy browns and ochres to vibrant yellows and greens. With my images containing many yellows, greens and peach shades, these were my main focus to produce.

Additionally, I scoured the coastline for seaweeds such as kelp and bladderwrack. These seaweeds offered a unique range of colours and I was able to produce soft shades of peach. Harvesting these seaweeds responsibly, being mindful of sustainability and ecosystem preservation, was a priority during my foraging expeditions.

Once the dye materials were collected, the next step was to prepare them for the dyeing process. This typically involved cleaning, chopping, and extracting colour from the plant materials by simmering them in water over a number of days. The resulting liquid, called the dye bath, would be used to dye the hand-spun Icelandic fleece.

Before coming to Iceland I had spun and mordanted 20 hanks of yarn ready for the dye pot. To dye the yarn, I submerged it in the dye bath with the plant materials still present and gently simmered it for around 30 minutes. The fibre absorbed the natural dyes, resulting in beautifully nuanced colours that reflected the surrounding landscapes and seascapes.

After dyeing, the yarn was rinsed, dried, and ready for weaving. The colours obtained from the foraged plants and seaweeds had an organic and earthy quality, reflecting the unique palette of the northern Icelandic landscapes.

4. Exploring Indigo: Dyeing and Over-Dyeing Yarn:

If you've seen any of my work in the past you'll know that I tend to use blue a lot! It's a tricky shade to create with plants especially Icelandic ones in May, so I brought a small amount of organic indigo powder with me to help out.

Indigo dyeing with a fructose vat is a method of dyeing that uses fructose, a type of sugar, as the reducing agent to create a dye bath for indigo. This process is an alternative to using chemical reducing agents such as sodium hydrosulfite or thiourea dioxide. Fructose vats are considered more environmentally friendly and can produce beautiful shades of indigo blue.

Here's a general overview of my process:

I prepared my yarn by scouring it thoroughly to remove any impurities which could interfere with the dye uptake.

I created the fructose vat by dissolving the indigo powder, fructose, and alkali in warm water.

I stirred the vat gently to dissolve the ingredients. It was important to avoid introducing excessive oxygen into the vat as it can hinder reduction.

I allowed the vat to sit undisturbed for several hours for the reduction process to take place. During this time, the fructose acted as a reducing agent, converting the indigo to its soluble and colourless form.

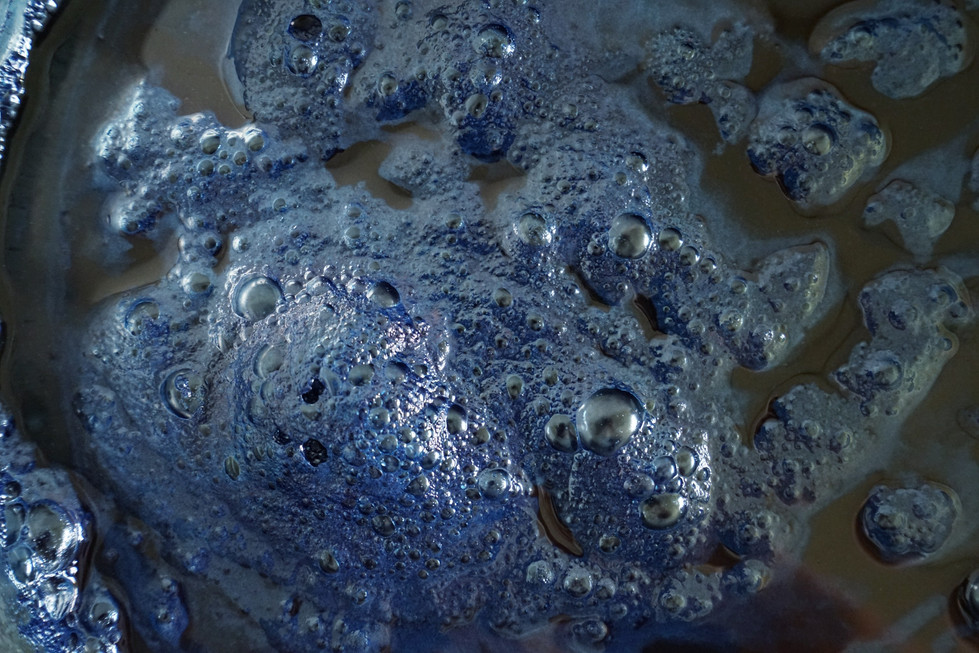

Once the vat had sufficiently reduced, it appeared yellowish-green on the surface. At this point, it was ready for dyeing.

I soaked my yarn in water overnight before immersing it into the vat. I used a colander to make sure the yarn was fully submersed but not touching the sediment at the bottom of the vat.

After 30 seconds, I lifted the yarn out of the vat and gently squeezed out any excess water.

When I removed the yarn from the vat, it initially appeared a yellow-green shade but as the indigo came into contact with the air, it gradually began to turn blue.

I let the yarn hang for a while before rinsing it in clean water then repeating the dipping process a number of times until the colour reached a deep enough shade.

I dyed a number of hanks of yarn with the indigo to create a gradient of shades but I also wanted to have a few shades of green/aqua so used a few of my plant dyed yarns to overdye with the indigo. This gave me a range of coordinating colours to use as weft yarns later on in the residency.

5. The Wool Washery in Blonduos:

One of the main highlights of my first week in Iceland was witnessing the wool washing process firsthand during one of the visits organised by the Textile Centre to the local wool washery in Blonduos. The wool washery is housed in a restored historic building on the edge of the town. The facility is a crucial part of Iceland's ongoing efforts to preserve and promote its traditional textile industry and was a fascinating look into the work which goes into preserving a way of life for many Icelandic people.

The process had a number of stages to take the raw fleece to fibre ready to be spun and dyed:

The raw fleece was delivered to the wool washery on trucks after being collected from farms around Iceland.

It was put through a number of machines (a few built in the UK) where it underwent a meticulous cleansing procedure to remove dirt, grease, and impurities.

The washing process was repeated several times over in a long machine the length of the warehouse.

The now clean fibre was then sent through overhead tubes to a room where it was blown dry and dropped from the roof into a large pile.

The final stage was for the clean and dry fibre to be packaged into bales and stacked, ready to be sent on to the spinning, dyeing and processing factories.

We were given a few bags of clean wool each to take back to the textile centre and work with which was a nice surprise.

7. A Global Community of Artists:

There were twelve artists taking part in the residency during May, from countries around the world (but mostly America!). It was such a refreshing change to work in an more communal environment and I was very lucky to be with such a welcoming group.

It was interesting to hear about textile practices so different from my own, the UK can feel like a bit of a bubble sometimes and it was refreshing to hear new perspectives. I was able to exchange ideas and get second opinions from others who had been in the textile world for a lot longer than I had and who had experience in areas I hadn't even considered until now. I also found it interesting to talk to the residents who had a more academic background in textiles. They had a very different viewpoint and it was interesting to talk about textile and woven design as a concept rather than thinking about it as purely a business.

I also really enjoyed having company during the day for the non textile related activities like hikes, Eurovision watching and of course, trips to the local swimming pool. Spending hours floating in a geothermally heated outdoor pool whilst it was snowing was definitely a first for me!

8. The Culmination: End-of-Month Exhibition: 'Snowbreaker'

During the final weekend in May the resident artists displayed work in and out of the textile centre buildings. It was really nice to see what everyone had been working on over the past four weeks. The work was diverse, from embroidered samples to fashion pieces to conceptual installations. Many of the designs on display incorporated influences from the local landscapes or included raw materials which had been sourced locally.

I displayed my handspun and plant/indigo dyed yarns as gradient circles. Seeing the yarn hanks together in this way gave me a good idea of the types of landscapes I should be able to weave it into in June. My first sample piece woven on the TC2 jacquard loom was also on display.

This first month in Blonduos has been a whirlwind of creation, experimentation and discovery. I've made friends which I'm already planning to visit (and possibly collaborate with) in the future and feel like I have a much better idea of what I'd like to achieve with my creative practice. It's been wonderful to see a different side of weaving and take an in-depth look into the Icelandic textile industry. June will be a month spent weaving at the loom, I can't wait to see what my wool will become!

To view additional content from my residency trip, you can contribute to my fundraiser at https://www.ko-fi.com/arratextiles. By doing so, you'll gain access to an online version of my 143-page Textile Residency Photo Book, which provides a detailed account of the 10-week journey and offers a more personal perspective on the experience.

If you would like to keep up to date with the day to day of my textile practice find me on Instagram through the link below.

Enhance your wardrobe with versatile Yellowstone Clothing that blends comfort and timeless Western fashion. Complete the look with Yellowstone Dutton Ranch Merchandise, a must-have for true Yellowstone fans. Shop authentic styles and durable designs exclusively from Western Apparel.

So interesting to read how and where you get your inspiration from - really enjoy your blog Lucy

Lucy , so glad for you . What an amazing opportunity! Enjoy